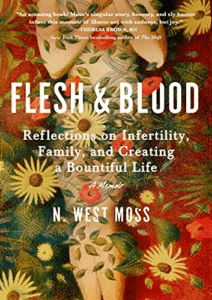

N. West Moss and I taught together at Montclair State University. West has gone on to wonderful writing projects, including her memoir to be published on October 12th by Algonquin Press. Here is my review:

—–

Hey! Would you like to talk about heavy menstrual flow, hysterectomies, and infertility for a while? Don’t run away. N. West Moss’s story is mounted on the quilted scaffolding of loving family, wise and bold social commentary, and is a pleasure to read.

The tale is told in short, fast-paced chapters which flow from one subject to another. There is no trudging around in the muck. One chapter is about grandma’s calendar, the next is about a felled pine tree, the following about the family history in New Orleans. Moss’s dire condition lends heft and interest to all the descriptions, definitions, and experiences of her tale. At some points, she seems close to dying, but then the story turns to gin and tonics or ducks or poetry.

Moss’s world is peopled by fine, generous people, from nurturers long gone but fondly remembered, to her husband, parents, and the monks next door. She doesn’t like fuss, so asks her many concerned friends to send her an outline of their hands, and their responses cover her wall, each tailored to give her special solace. How many times have you sent an outline of your hand to a friend in need? How many times has a person asked for such a thing? Moss lives a creative, original life. None of her setbacks drown her spirit. They won’t drown yours either.

Every now and again, Moss drops a finely-honed nugget of wisdom: “There is something about me not needing anything that makes people especially generous. It’s the needy people we shy away from…the people who are always reaching toward us who make us lean away,” or “Devout little atheist that I am, I cannot help being moved when [the monk] says, ‘We are praying for you.’ He has memorized the date of my surgery. He will pray. Love is love, and I’ll drink it from a stream or from an old paper cup, I don’t care which.”

Prepare to love the many colors of life as she paints it: the paean to a praying mantis, the missing straw hat on a limb, the rare medical condition, the nimbly wise husband, the abiding presence of Grandma Hastings and her mother before her, and the little baby girl that only lived a week. You will join Moss in mourning this little girl who died before the turn of the century. The 20th century.

Under “complaints,” I would list Moss’s authorial decision to switch to the present tense as a method of bringing the reader into the moment. This reader was jarred by the switch. A couple of times the timeline was unclear, but this book exists in Moss’s head and there is a magic to it that transcends time lines. The quibbles are barely worth the time spent to write about them.

Moss’s finesse turns this blood-soaked tale into comedy, or comedia. Life is happy and sad at the same time, or, more accurately, hilarious and heart-breaking.

A decent book review makes comparisons of the book under consideration with other books, but none came to mind. She is not Malcolm Gladwell or David Sedaris, neither Anais Ninn nor Joan Didion. She is humbly herself, and that is more than enough.

If you want a taste of her style, I recommend Chapter Forty-Five: Going Home.

Oh, and it reads like a thriller, too. Now there’s a phenomenon—a page-turner about menstrual blood, a hysterectomy and infertility.