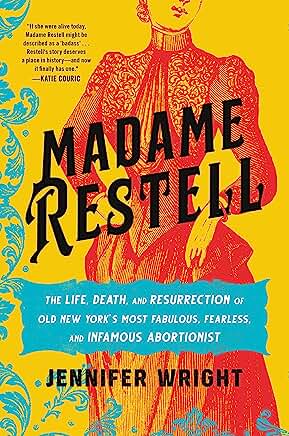

Jennifer Wright’s new book, Madame Restell: The Life, Death, and Resurrection of Old New York’s Most Fabulous, Fearless, and Infamous Abortionist gave me insight into my own family’s history. My great-great-grandmother gave birth to six children, three of whom survived. One died in infancy, another fell off a grape arbor when she was six, the third died of wounds sustained in the Civil War. Her son, my great grandfather, had four children, one of whom died in infancy. That’s how things rolled in America in the 19th century, when the industrial revolution was drawing young women from farms into factories and cities.

After my great-great grandfather died of a sudden fever, his widow took in laundry, which I learned from this book was safer than being a laundress for a private family where she could be used sexually by her employer with no consequences for him and no support for her if she got pregnant. Wright tells such a tale—the pregnant employee was dumped into the street, the male employer was regarded as having made a single unfortunate mistake.

In 19th century America, life was tough for women in ways that 21st century folk will find hard to imagine, but we are challenged to confront the details in this assiduously researched book.

Madame Restell scandalized New York City for many decades at a time when one out of every four or five women had an abortion, only slightly fewer than today. Pregnancy was more dangerous then, and estimates are that around twenty of every thousand childbirths ended in maternal death. By comparison, estimates today range around twenty for every one hundred thousand. For women who wanted or needed an abortion to beat those odds, Restell manufactured and sold abortifacient powders and pills and performed thousands of surgical abortions over her long career. There is no record of her ever having lost a patient, though some women who later became ill with an unrelated disease such as tuberculosis blamed it on the abortion. Given her reputation as a skillful practitioner of spotless discretion, her clientele from every social stratum showed up in a steady stream at her office. She provided services for the poor at a reduced rate, sometimes free.

Her ostentatious wealth made her a target, and she was a particular target of Anthony Comstock, who inspired the Comstock Laws which forbade contraception, abortion, and “smut.” Strict laws and personal persecution did little to reduce the number of women who had abortions. Lawsuits and stints in jail did not reduce Madame Restell’s determination to perform them.

Wright acknowledges many helpers in researching this book, from the Research Services department of the New York Public Library to a squad of fact-checkers. The facts that form the skeleton of the book are so shocking that the 30 pages of endnotes are necessary. Otherwise, readers might not believe that working women drugged their babies with laudanum or placed them in “baby farms” or foundling homes where over 90% of them died, or that scientists said that women’s limited capacities were because they had smaller skulls then men. The details are savory.

Wright reserves the final chapter for her own story of nearly fatal childbirth, and states the obvious fact that “Motherhood in and of itself is an act of bravery, even if you choose it with pure joy.”

Knowing that women have been outrageously misused in other eras is only slightly comforting when confronting the struggles of today. Looking at the devastation that we could be going backward towards is a cautionary tale indeed.